Context

Our team worked with the city’s child welfare agency to design a more dignified referral experience for families and agency staff, while developing a culture and practice of family-centered design and decision making.

My roles

Carving out space for families and front-line staff

“No, we don’t do that. We don’t want to get yelled at.”

This was the initial response from agency leadership, legal, and union reps when we proposed engaging families, front-line staff as research participants and co-designers.

I moved them from No to Yes by inviting agency leaders to participate in early discovery workshops and sit for user interviews. They felt included in the process, and got to see first-hand how design research was different from how the agency typically engaged its clients and providers. Leadership buy-in led to staff buy-in, and staff buy-in opened the door for us to connect with service providers and eventually with families.

That top-down buy-in (often bordering on excitement) allowed us to engage 80+ parents and over 100 staff in research and co-design activities, where families and staff helped ideate, iterate, and validate research artifacts and prototypes for service enhancements.

Just as importantly, it gave us a real opportunity to demonstrate what a more inclusive and deomcratized process for program design and decision making looks like.

One of our partners leading a discovery research session with a child-welfare affected parent.

We created a set of design principles to guide and ground our work moving forward.

Enabling the enablers

Our early discovery research showed that families had very little agency in the referral process. The key drivers of the process were the child welfare investigators and back-office agency referral staff. Working with these other teams was outside our initial scope, but integral our work. In order to support the family referral experience, we needed to support the other people who were part of that experience.

Improving family experience was our primary objective, which meant supporting more family-centric ways of working for the CPS workers and referral consultants who drove the referral process.

This Jobs Board used rubber bands to represent the tensions between staff’s formal and informal roles and responsibilities, including service referrals.

Service blueprinting helped us pinpoint opportunity areas to support family and staff, and helped us make the case to bring new partners to the table.

Reframing to entice new partners

I pitched leaders from those other divisions to bring their teams into the project so we could properly address the end-to-end family experience. They were hesitant. Their staffs were overworked and they didn't see any value-add. I presented our work as an opportunity for those teams to address their own needs.

For example. child welfare investigators were being asked to “sell” Prevention Services to their clients without proper training, tools, or supports. Our work would help our partners at the Division of Prevention fill that gap, providing the tools and supports that investigators so badly needed to better serve their clients, cut down on clerical inefficiencies, and save time.

Their leadership bought in, which allowed us to co-design, test, and iterate towards a family-centered common language, and tools to support investigators “making the sell” for Prevention services.

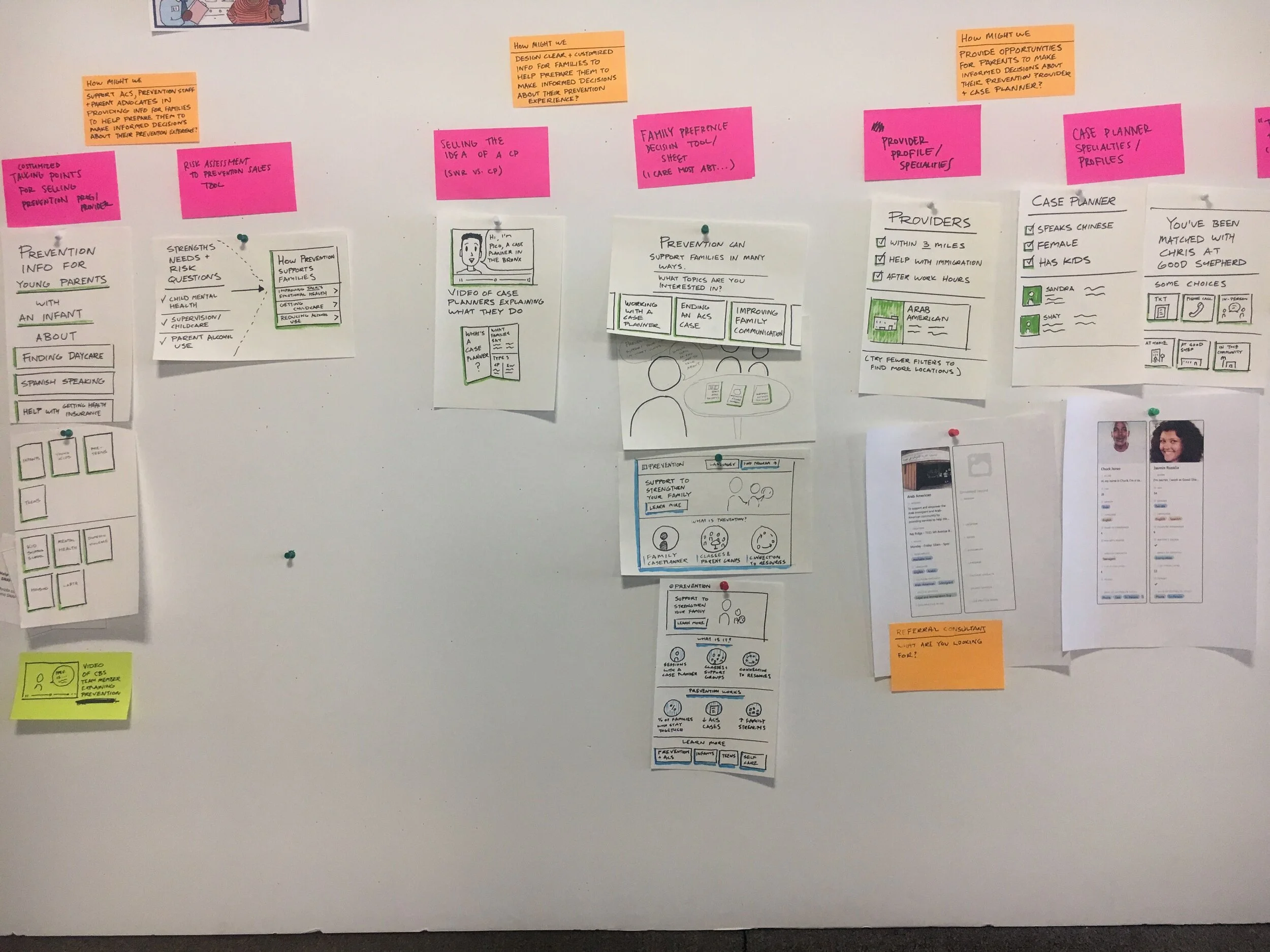

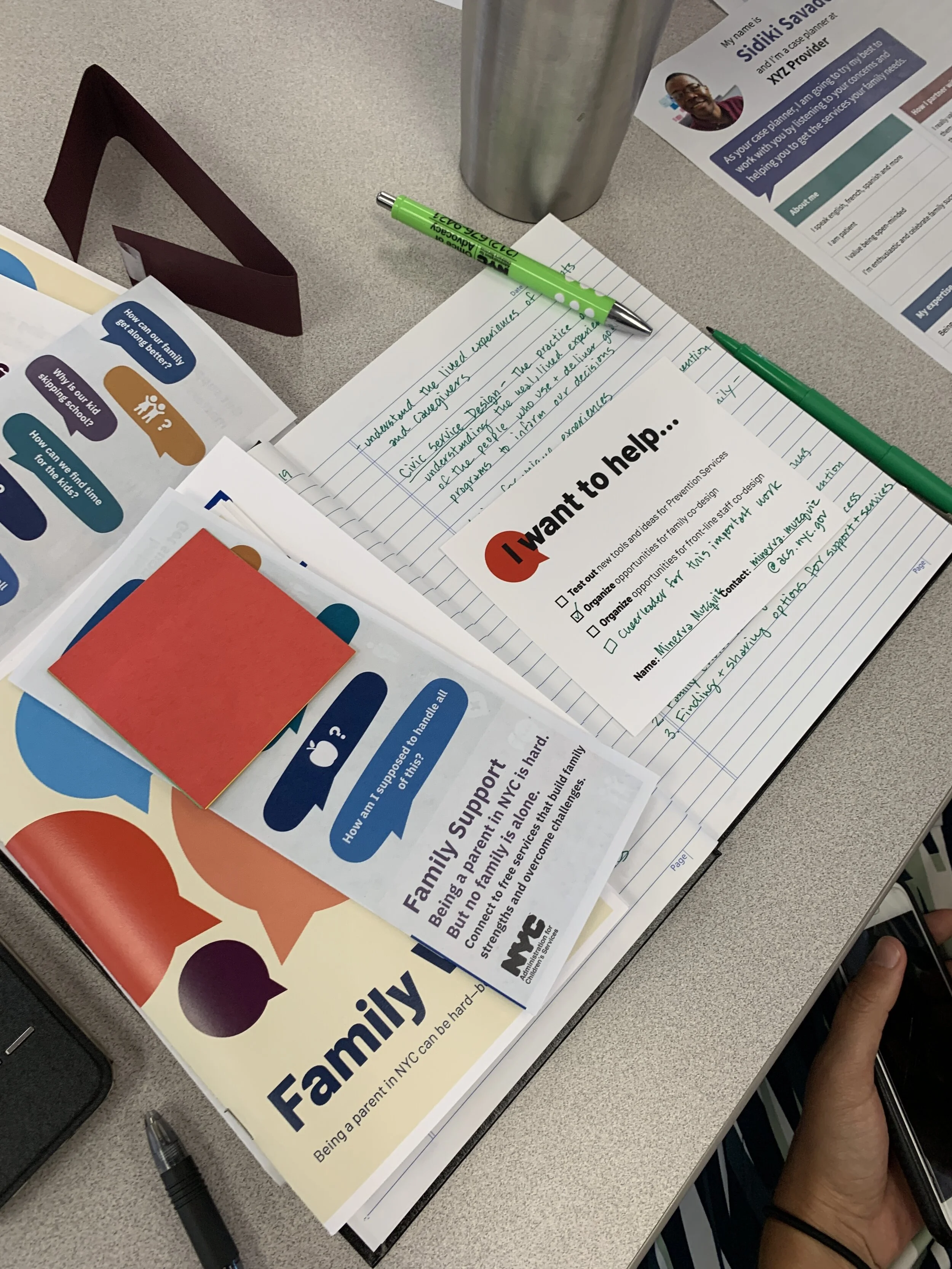

Co-design workshops brought together providers, agency staff, and parent advocates to ideate around our research insights and opportunity statements.

Defining a family-centered strategy

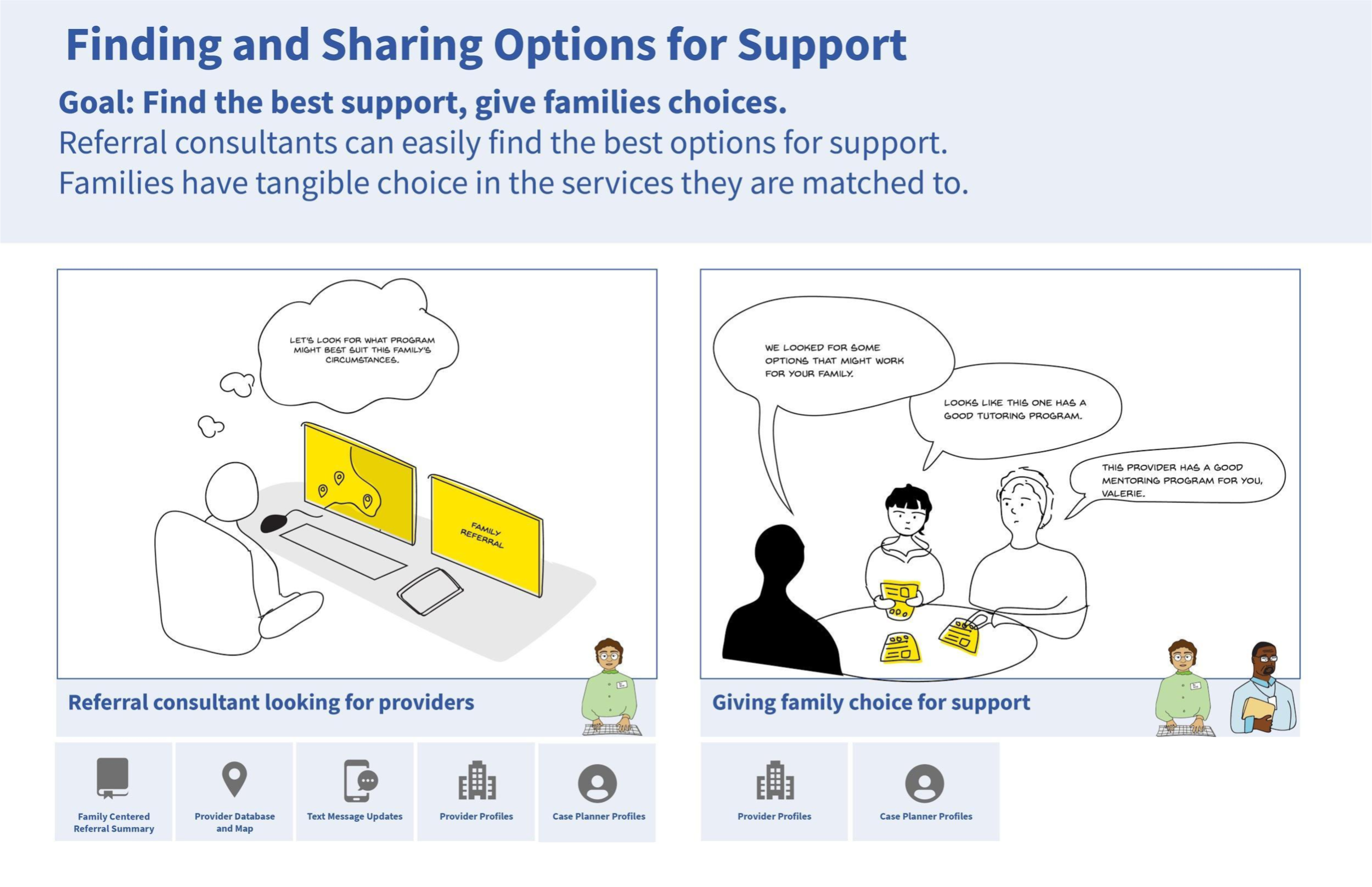

Based on our work with families and stakeholders across the agency, we developed a vision for a future where families have authentic choices about the services they receive, where they receive them, and the case planner they work with. I worked with our agency partners to put together a phased approach that would allow the agency to build incrementally towards that vision.

Now

New language and tools to help a family understand and get excited about Prevention Services.Near

Families have the opportunity to indicate preferences around prevention program, provider, and case planner.Next

Families have the opportunity to choose program, provider, and case planner from set of available options.

With the vision in place our team engaged families and staff in prototyping sprints to bring the vision to life.

We defined a set of key moments for a future family-centered referral experience. We used used these moments to ground our prototyping work.

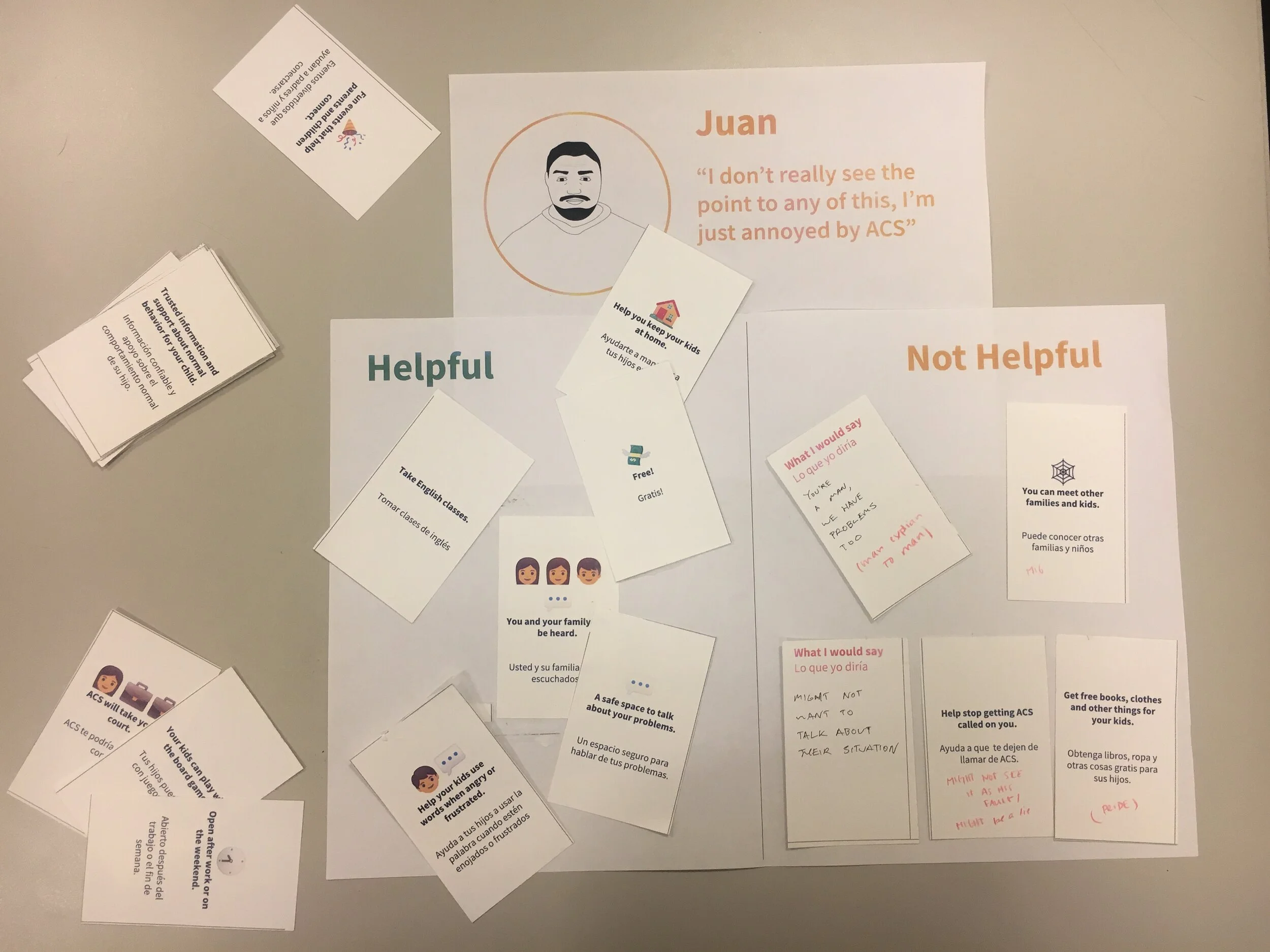

CPS workers and families each had limited understanding of what Prevention Services actually do for families. We used generative activities to work with families to learn how they talk about the value of services, and how they would “make the sale” to a friend or neighbor.

We created a family-centered common language to help align all stakeholders, and a suite of informational materials and interactive tools to support family-centered conversations between CPS workers and families during the referral process.

Turning concepts into systems

As other members of our team worked with families and front-line staff to co-design tools to support their experience, I worked with agency leaders and back-office staff to co-design the backstage systems and processes that would need to be in place to enable that family-led referral experience. We used the following questions to help guide our thinking:

What are the roles and responsibilities that would be impacted?

What are the processes that would be impacted?

What technology would be involved?

What data and information would be needed?

What would be the impacts on measurement and evaluation?

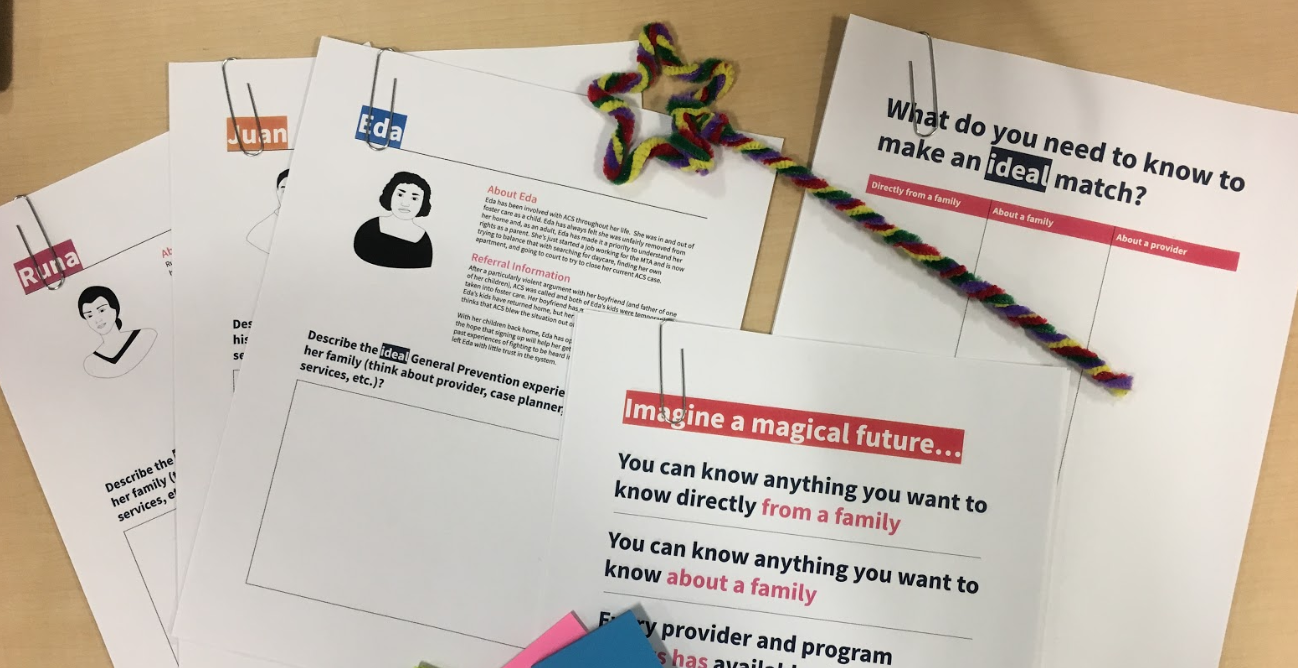

For example. I worked with agency referral staff to define what information they needed to make better referrals for families, where that information might come from, and how it might be presented.

Together we moved from a manual process filled with clogged inboxes, excel trackers, and inconsistent documentation towards a vision for a streamlined referral system that would allow staff to focus on families instead of managing bureaucracy.

Personas helped ground a generative exercise with referral staff to surface all the information they would want to make a good referral for a family. And a little magic always helps to give public servants permission to dream.

Early prototype for a new family-facing referral packet included all the information referral staff need, from both families and investigators, to make good referrals.

We moved from a manual process filled with clogged inboxes, excel trackers, and inconsistent documentation towards a vision for a streamlined referral system that would allow staff to focus on families instead of managing bureaucracy.

Laying foundations for implementation

I set up weekly convenings with champions of our work across the agency, which I called the “Integration Leadership Council.” This was a way for us to keep agency leaders up to speed and excited about our work while also opening up inroads with existing funded work streams where our work might come to life.

As we started to hone in on how the agency might pilot some of our work, we developed training and change management materials to help support behavior change and drive adoption for key roles in the referral experience.

We created story boards for key moments in the future family-centered referral experience to make it easy for our partners to share the strategy across the agency.

To support adoption and behavior change, we built training plans and materials for each staff role, including an introduction to new tools, conversation scripts, and potential positive impacts for performance indicators.

Storytelling towards the future

I managed our team’s creation of storytelling assets and implementation roadmaps, and set up and facilitated hand-off workshops with agency decision makers and managers, funders, and vendors to help our partners continue to push the work forward.

We included these “I want to help” cards during our hand-off workshops as a way to capture staff enthusiasm and generate opportunities to keep moving the work forward.

Key outcomes

Our research and future vision informed the agencies recent $220 million dollar contract for the next ten years of Prevention Services in NYC, where Family Choice is one of the three major areas of improvement.

Our prototype for a digital referral platform was turned into a multi-million dollar RFP to procure new referral management technology.

Our partner team continues to use and spread design methods to bring families and staff into decision making processes. They were even able create a role for a service designer on their team.